Pripyat, the Green City

Today we’ll be looking at photos of despair and beauty, from the Sarcophagus (the cover protecting the damaged fourth block of the Chernobyl nuclear reactor) and the perished city of Pripyat, one of the most photogenic places on Earth.

It is an object of many names. The Sarcophagus. The Shelter. The Об´єкт укриття… and it can be viewed from many angles—engineering, aesthetics, the human angle, and more. Its construction began in June of 1986 (in other words it was drawn up in just a few weeks) and it was ready in November of that year. Ninety thousand workers took part in its construction, and another 100 thousand in decontaminating the region.

In his book “Memories of Lives Given,” Alexander Kupny, the former head construction engineer for the Sarcophagus, describes the group of Azerbaijani workers who were assembling the crane to be used for building the Sarcophagous. Short on time, they built it directly next to the damaged reactor. The crane got assembled… but not one of those men is living today. In short, many people sacrificed their lives for the Sarcophagus, whether consciously or not.

Where It All Started

After the initial wave of interest, attention, and cash, came the years when this structure, built quickly and basically via remote control, started to decay—as seen on industrial cameras. Water was getting into it, and radioactive dust was escaping out of it. In 1993, Photographer Gerd Ludwig, shooting for National Geographic, was the first western photographer to capture it on film. Since then he has constantly been returning to document the Zone and phenomena surrounding it, such as people with post-Chernobyl medical problems, or the construction of the new reactor cover. He exhibits these photos at The Long Shadow of Chernobyl.

In 1997–2007, a number of measures was taken to stabilize the Sarcophagus from within and without. They extended its life by 15 years. Keep in mind that 95% of the radioactive fuel is still inside, and that radioactivity, among other damaging effects, corrodes metals. Also keep in mind that the Chernobyl catastrophe’s story is not over. As long as there is fuel in there, the situation cannot be considered solved and stable.

Now imagine how strange I and the rest of the documentary team felt here, among the vehicles of the Novarka construction consortium, standing before a monument showing the Sarcophagus held in a giant hand. And the colossus itself, behind several fences, feeling rather distant. In the shadow of the gatehouse three workmen smoke and nervously turn their heads towards us.

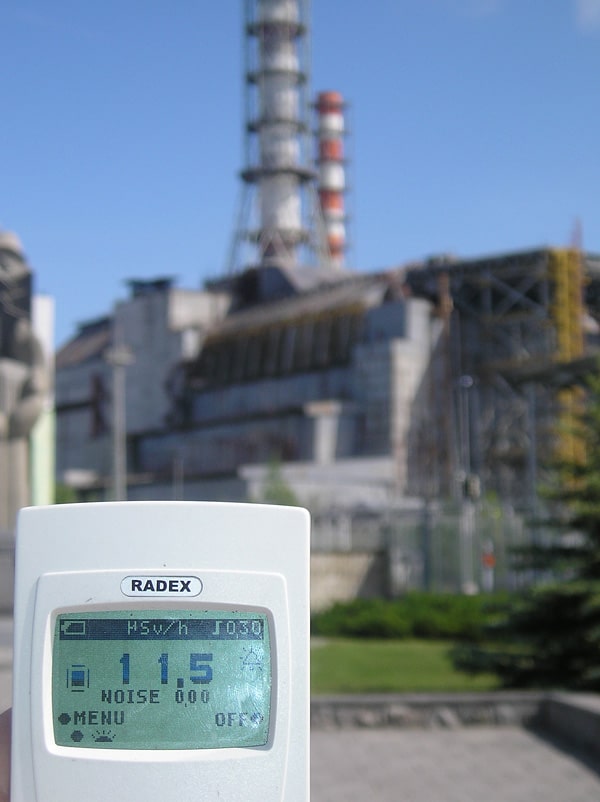

When we pull out the dosimeter, it’s clear why they are relaxing on this side of the gatehouse: the radiation level here, two to three hundred meters from the epicenter, is over 10 microsieverts (10 µSv) an hour. And that’s not radiation coming from the ground—this dirt has been perfectly decontaminated. It’s gamma radiation from atoms being split right inside the Sarcophagus. The ideal workplace! Radiation intensity falls with the square of distance, so where we’re standing we’re safe, but things must be pretty wild under those rusty gray walls. Our guide Oksana demonstrates for us what happens when the dosimeter is placed behind the granite memorial—the value measured drops by half.

It’s all so absurd. I try to stop and concentrate for at least a short while—to focus on details. I try using a long lens to capture an interesting detail and compose it with no distracting objects in the way. Then just to be sure I also take a shot of the whole scene. Then I drop the matter, drop the camera in my bag. I want to look with my eyes and be alone. Naturally throughout all this I’m hearing a symphony for two dosimeters, so any kind of tuning into the site’s spiritual energy is out of the question.

We also take some group photos. In my mind I’m crossing one more off my bucket list: Baikal, Giza, Chernobyl. I look forward to coming back here with an invitation straight from the power plant and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development backing me, and walking right through this foreboding gatehouse, right into the inside.

The next stop is the nearby Red Forest (Рижний лис). The largest batch of fuel chucked from the blazing reactor landed right here. The guide is not thrilled to let us out of the car in this location. The dosimeters scream with joy, and we’ve got ourselves a record—58 µSv/h. And that’s while standing on the road. But we don’t see any twisted trees or red bark, or in fact, even enough trees at all to call this place a forest. One of my advance plans had been to create a study of tree types on a large-format Arca. I began taking training shots for this work already before entering the Zone. When I do get to step into the Red Forest one day, it will pay off.

Dressed in Green

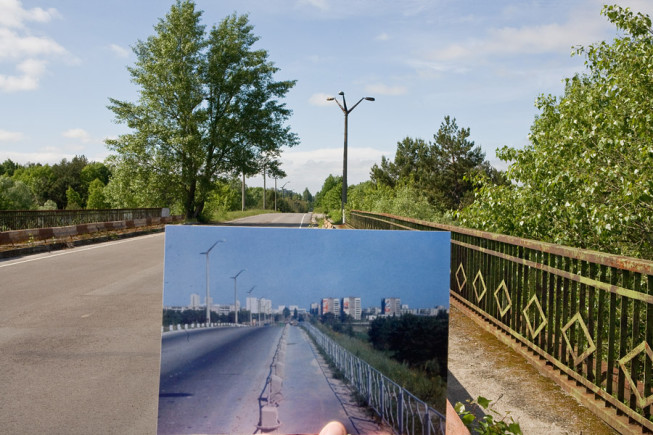

Only one more inbetween stop awaits us—the Bridge of Death. Just before Pripyat there is a rail overpass among completely flat countryside, the only option around for getting a view from above. My view is degraded (enhanced?) by the full-grown leaves of May. A legend states that when citizens of Pripyat went here to see what happened in the power plant, the ones standing at the end closer to the plant died within a few weeks from acute radiation poisoning, while the ones closer to the city survived. This may be true, though it’s hard to say if one bridgelength really decided life and death.

But what was evident from the bridge was Pripyat’s nearness to the plant: truly only two or three kilometers as the crow flies. Today the area is quite overgrown with trees, but the thought of waking up in the morning, seeing the plant from the window, getting on the bus, riding to the plant, working my eight hours, and having dinner with the same view, doesn’t fill me with a lust for life. Maybe that’s why this city was so full of parks and of sports and cultural facilities.

Nowadays the gate to the city is a gatehouse. Beyond the barrier and a pack of dogs, a Christ on a cross welcome visitors. There are no longer roses here, but the city doesn’t lack for refreshing green colors. Actually, it’s not at all obvious that we are in what once was a city. The buildings merely glint through among the full-grown poplars and sundry bushes. I know asphalt roads like this one from forests in my own country.

We stop by a monument to the Soviet Republics, by a hospital, by the Pripyat Café with its view of a dead branch of the Pripyat River. In each of these and other places, I hide a tiny surprise—a small piece of dental x-ray film. I photograph their position and record the radiation level. In autumn I’ll retrieve and develop them—I may only need a fixative—and play with these direct recordings of radiation from the Zone. If it works. This is all just theory for now.

Discovering this city by foot is better than riding in a car. It’s time to sort out my impressions so I’m not swamped by the number of objects and subjects to photograph. I toy in my imagination with making Pripyat a photo-reservation. It’s not good for anything else anyway. Visitors would only be allowed in with a DSLR and a minimum of two lenses and at least a 32 GB card.

Permission would always be granted to large groups, early in the morning. Nobody would be permitted to leave the city until their card was full. It would erased at day’s end right before the photographer. No replacements. In my opinion this is the only way to defeat the hellish spirit that impels everyone to photograph everything.

Pripyat is a beautiful city today. I wouldn’t hesitate to say it could be a model for other cities and an inspiration for urban planners. You can walk here all day without being disturbed, and you’re always among the trees. And yet, in the city…