Mechanical vs. electronic shutter: what are the differences and which one should you use?

Analog technologies are becoming digital. Rolls of film have been replaced by an electronic sensor, and moving mirrors are also slowly becoming obsolete. Yet, there is still one last remaining bit of the past to be replaced: the shutter. The technology here has not yet reached the necessary heights to go completely digital, so there are cameras that allow you to choose between a mechanical and an electronic shutter for each image. Each has its own pros and cons.

Mechanical shutters have been around for some time and, while their time too will come to an end, they aren’t completely ready to be replaced by their electronic counterpart. Some cameras allow their users to switch back and forth between different types of shutters according to their needs. Before we get to why, let’s look at exactly what a shutter is and what it does.

Firstly, just a note – other types of shutters do exist, such as central or lens-plane shutters. These, however, are quite out of the ordinary and go beyond the reach of this article.

Mechanical shutters

The sensor itself (or in the past, film) takes in light, but something needs to start and stop this process. That’s what the shutter is for. Mechanical systems come in many forms. Today, in about 99% of cases, you’ll encounter a system that consists of two curtains – the first curtain starts the exposure and the second curtain stops it. Technically, there are two sets of curtains with several individual blades in each set. They are most often referred to as first and second curtain shutters.

The curtains move rapidly and at the end, stop abruptly. This is where their biggest problem lies: their movement causes camera shake. Because their parts are lightweight, they do not have much force and you frequently won’t even notice this issue. However, when using a telephoto lens with modern sensors and a high number of megapixels, even a tiny amount of camera shake is noticeable. Not even a delayed shutter release will help you because the impact of the curtain shutters will always happen at the beginning of the exposure (and again at the end, when it doesn’t matter anymore).

There is another problem here with flash and very fast shutter speeds. Even if the curtains are fast, they have their limits. So, with extremely fast shutter speeds, such as 1/4000s, the first one opens and exposes the sensor and the second one doesn’t wait for the first one to close, but opens after a short pause, when the sensor is covered again.

This process in and of itself is not a problem, but in combination with the flash, you’ll find that there isn’t enough time for the flash to go off. Whenever this happens, its light will only illuminate the part of the sensor that was just exposed, leaving the rest of it in the dark. This situation is handled by using unique flash programs which aren’t always available and if they are, they are less efficient. We are not analyzing this specific issue in this article, because the other types of shutters described have the same problem too. Perhaps, new innovations are on the horizon to resolve it.

Due to shutter movement, there is also a limited number of frames per second. In short, moving parts cannot move infinitely fast.

Mechanical shutters also have a lifespan, meaning they can go bad and require camera service. Chance also plays a role here. For some cameras, the shutter curtains can fall apart after 100,000 photos, while others continue to photograph with millions of photos under their belt.

Electronic shutters

It may seem like a great idea to move on from mechanical curtain shutters altogether and simply turn on the sensor electronically and read its result. That is, the number of photons in each pixel. It’s certainly a good start, and this is exactly how an electronic shutter works. Unfortunately, even here, things aren’t so simple.

In today’s most frequently-used CMOS sensors, image data is read line by line. This reading of image data takes a surprisingly long time. While mechanical shutter curtains are able to complete an exposure in approximately 1/200 second, the electronic ones take about 1/30 second to complete the operation and read the number of photons from the entire sensor. It depends on the exact device. Logically, more expensive and newer ones are typically faster.

The whole situation can be compared to a scanner that reads row by row. However, instead of a document, it scans a moving scene, which can cause problems.

If you are shooting a moving subject or if you move the camera from side to side while shooting, the picture will be crooked, various distortions will appear, or in the case of video, you’ll get the “jello” effect.

Another unsightly effect appears in spaces lit by rapidly blinking lights (light bulbs, LEDs). The lights change their intensity more rapidly than the sensor is able to read, so some rows capture the light while others don’t. A similar issue happened in the image with the fans, where some places are lit up by daylight and in other places, it’s combined with artificial light.

Electronic shutters cannot be used with flash.

For the readout speed to be as fast as possible, many manufacturers have opted to produce images with lower quality. For example, these images only read 12 bytes of data from each pixel rather than 14, which in turn, results in slightly more noise.

On the other hand, an electronic shutter has a less limited lifespan, doesn’t cause vibrations, and is capable of shooting many frames per second. It is completely silent even though the shooting itself isn’t completely free from sound. For instance, you’ll hear the closing of the aperture.

What if we were to combine the advantages of both types of shutters?

Electronic front/first curtain shutter (EFCS)

Some cameras have the ability to start the exposure electronically and complete it mechanically. This way, the sensor can take its time reading the photons in the dark. This is called the electronic front/first curtain shutter (EFCS).

The process is simple, particularly with mirrorless cameras, where the first curtain is already out of the way before beginning shooting. EFCS is available in DSLRs as well.

Now we’ve discovered a way to avoid vibrations and problems with slow readout. Unfortunately, however, everything is not all sunshine and rainbows.

EFCS is frequently meant for relatively slower shutter speeds, because with fast ones (1/4000s and higher), it can result in uneven image exposures. It’s complicated to coordinate both a mechanical and electronic path via the sensor. In some cases, banding can appear on the image.

What’s more, at faster speeds and with very bright lenses, it again results in worsened bokeh. The cause is a difference of a few millimeters in the distance from the mechanical blades and their electronic counterpart to the sensor. (You’ll find a more in-depth explanation here.)

Which type of shutter should you choose?

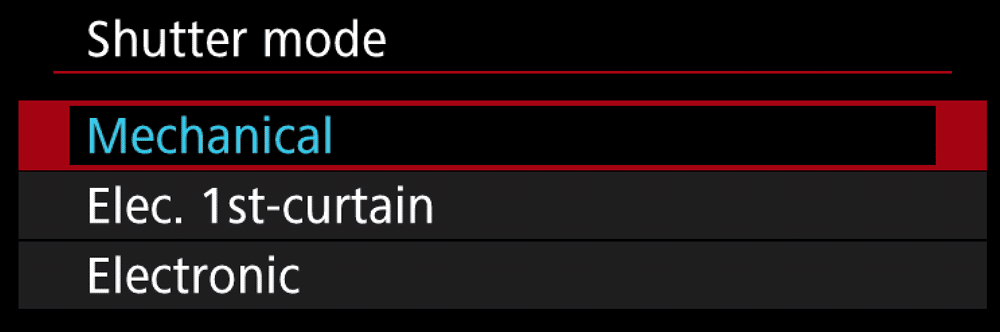

Many modern devices allow the choice between two or all three of the options listed above.

If you don’t want to risk it, the mechanical shutter is the safest choice. You won’t achieve superbly fast shooting and perhaps individual pixels will be slightly out of focus, but otherwise everything will work as expected.

For uncompromised quality, however, there are better options available to you. In the menu, you can sometimes find the option of auto-switching shutter modes where the processor makes the decision for you. With relatively slower speeds, it uses EFCS and with faster ones, it switches to the mechanical shutter. This, in turn, becomes your most versatile option.

If you don’t have this technology at your disposal, you have a decision to make. The concrete settings for individual shutters depend on the device so it is definitely worth a visit to the many online discussion forums. Typically, EFCS is a good initial choice. If you see problematic areas in the picture, there is always the option to go back to a mechanical shutter.

A fully-electronic shutter is ideal if you want to be as quiet as possible or if you require the maximum number of frames per second. Depending on the type of camera, you will pay for this privilege with somewhat higher noise and problems in artificial light.

The best of both worlds – global shutter

Camera manufacturers are gaining ground on a universally usable and electronic, “global” shutter which would manage to turn on all pixels at once and turn them off while simultaneously reading them. The issues described above would go away and we’d gain a universally usable system. This technology already exists – it is being used in a few select cameras. However, for now, it has more noise and other technical issues, so it’s still in the process of being perfected. It’ll take some time, so it’s a good idea to learn to use the technology we have at hand right now.