Portrait Lighting I: Keeping Quality, Intensity, and Light Temperature in Mind

Just about every photographer has tried portrait photography at some point. But many of them run into trouble when it comes to portrait lighting. There are several ways to go here. But for all of them, you have to keep in mind basic parameters such as the light’s intensity, quality, and color. Take a look at how to master these.

There are three light situations that you’ll encounter when shooting portraits.

- Studio photography with the use of artificial lighting.

- Outdoor photography with the use of natural light.

- A combination of natural light and artificial light when shooting in dark interiors.

Naturally this classification isn’t dogma; you can also use any light combination in all of the mentioned situations.

We’ll cover the individual cases in separate articles.

The Properties of Light

In general we can distinguish these properties for light:

- light intensity,

- light quality,

- light color,

- and light direction.

All of them fundamentally influence a portrait’s final look.

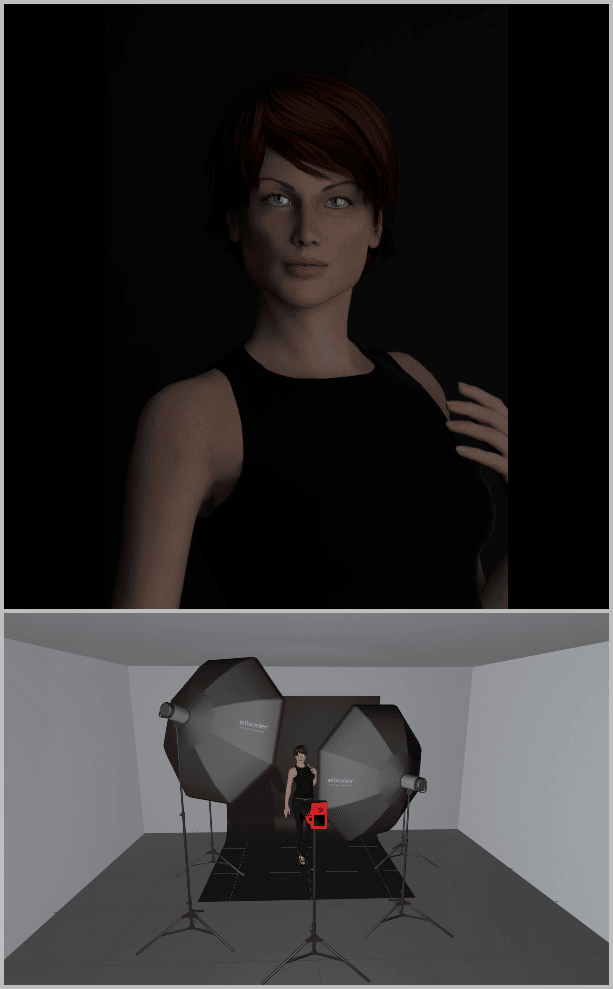

Light intensity influences a photo’s overall tonality. In most cases you want to have just enough light, so the photo is neither too light nor too dark. Portraits shot with low-key or high-key techniques are an exception here.

An exposure meter can help you to determine light’s intensity. When you’re taking pictures under permanent light (natural or artificial), you can make do with the exposure meter built in to your camera. But when you’re taking pictures using system flashes, etc., you’ll want to have a special external exposure meter.

If you don’t, you’ll have to rely on trial and error. Since you can preview your pictures immediately on the camera display, however, this isn’t a major problem today.

Light quality means how sharp or diffuse the light is. You use it to influence the portrait’s overall atmosphere.

For a romantic picture, use distinctly soft (diffuse) light; for a dramatic portrait, meanwhile, work with hard (sharp) light. For formal portraits, meanwhile, light between these two extremes works well.

There are a number of aids that can alter light quality. You can find out more about them in our other articles devoted to portrait lighting in various light situations.

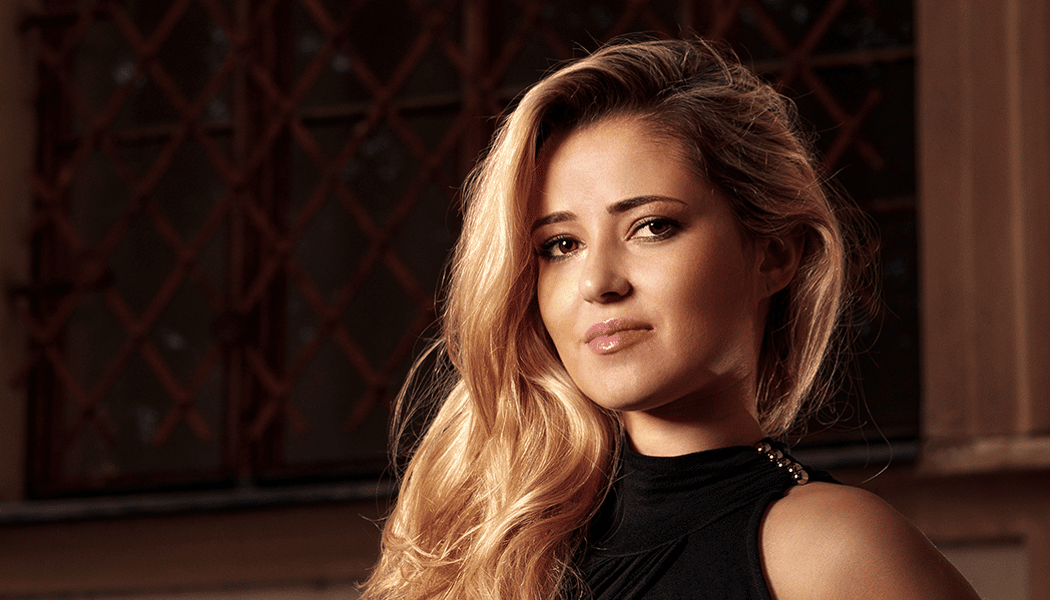

Through your choice of light color, you set the picture’s mood. Warm tones are optimistic and compliment the subject. A warm skin tone looks healthy in photos.

You should think twice before using a cold tone, and unless it’s an artistic intention, lean towards avoiding it.

For portraits, the light direction (the lighting pattern) has a fundamental influence on how they look. You can use the lighting pattern to manipulate reality very artfully and make the subject look good.

But a poorly chosen light direction can ruin the whole portrait. I’ll be discussing lighting patterns in more detail further on in the text.

The Different Kinds of Portrait Lights

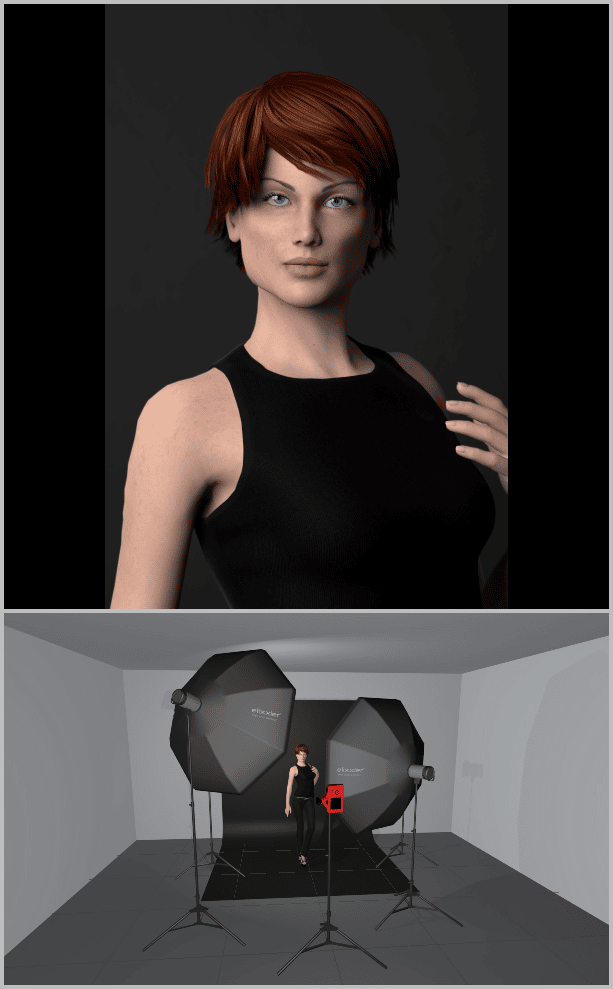

For basic photography, you can get by with a single light source, and some photographers do just that. But you can get much more interesting results by adding extra lights.

The basic light source is called the main or key light, and it is used to light up the subject’s face. When you’re lighting with it, keep in mind that the human face is visually complex, and light forms reflections and shadows on it. Light models the face this way, and the interplay of lights and shadows helps to make a photo look 3D.

Fill lights, or simply “fills,” serve to add light to deep shadows. These can be either extra light sources or reflections of the key light.

These lights have a lower intensity than the key light. The ratio of the main light’s intensity relative to the fills determines by how many exposure values the fill is weaker. Here are the ratios that are used the most:

- 2:1 (1 EV),

- 4:1 (2 EV),

- and 8:1 (3 EV).

The lower the ratio, the less shadowed and dramatic the portrait is.

Generally you need to retain shadows due to needing to keep the portrait looking 3D, but in one specific case you will run in to a 1:1 lighting ratio. This is used when photographing a model’s makeup (a beauty shot), where shadows can distort the work of her makeup artist.

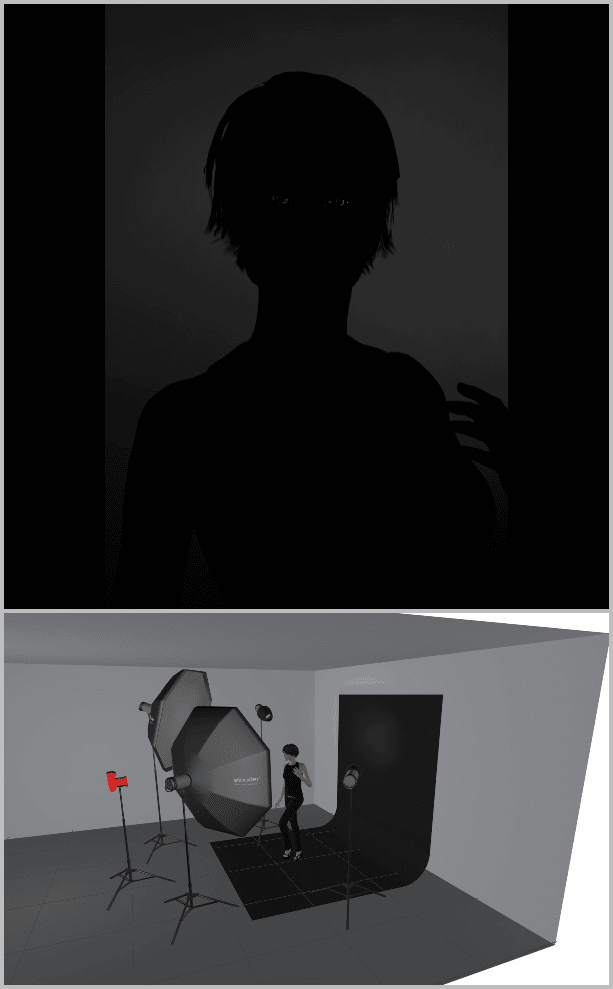

Rim and background lights separate the subject from their background. This is especially important when you’re photographing someone in dark clothing or with dark hair against a dark background. If you don’t separate these from the background, they will meld into it.

Two methods are used for separating the subject like this.

- You can light the background behind the subject (a background light).

- Or you can light the subject from behind and create contours on them (a rim light).

Hair lights and other effect lights help to make a portrait look special. They are most often used to illuminate hair and other specific parts of the subject.

Among travel photographs you’ll encounter portraits taken with a single light source, but in fashion magazines you’ll even find portraits where the photographer used over a dozen lights.

Learn to Put Lighting Angles to Work

The placement of the key light relative to the subject has a fundamental influence on a portrait. Several time-tested, stable lighting patterns exist for portrait lighting.

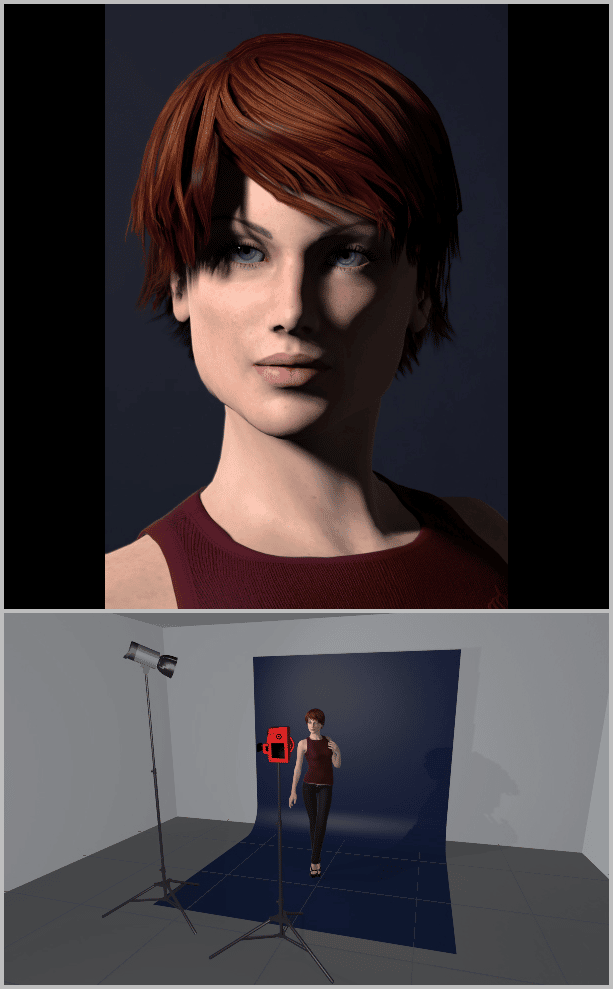

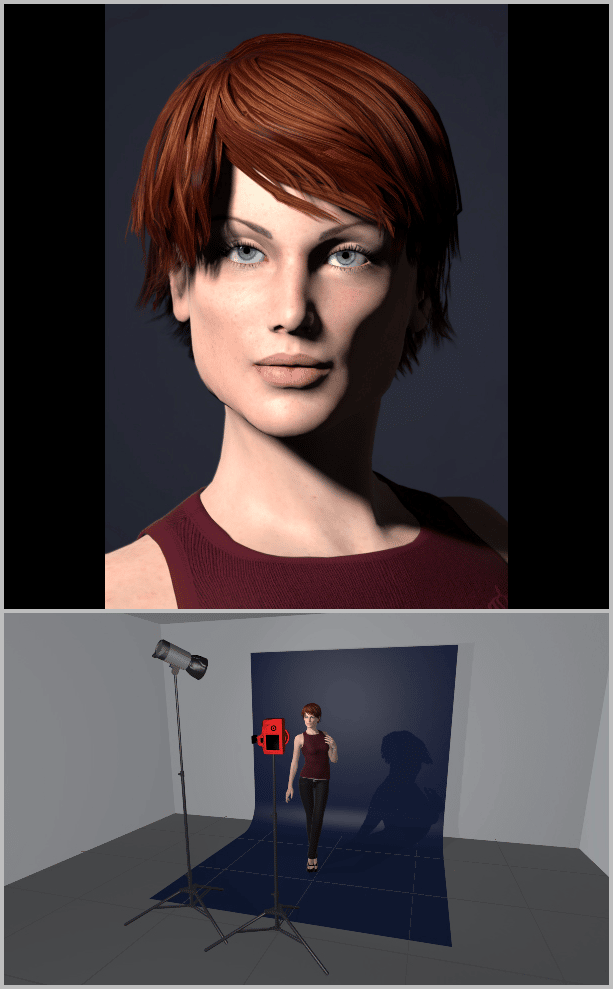

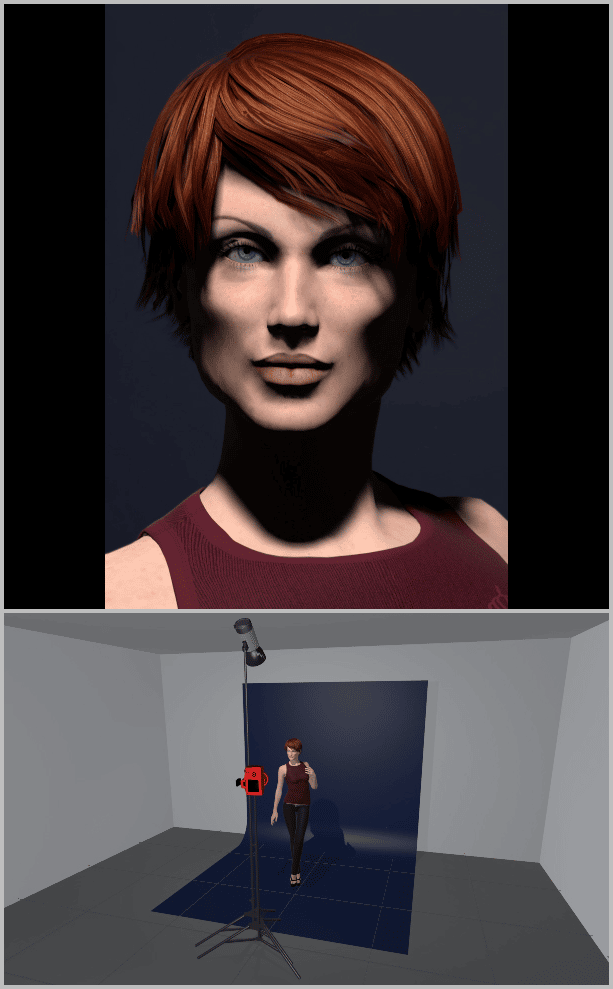

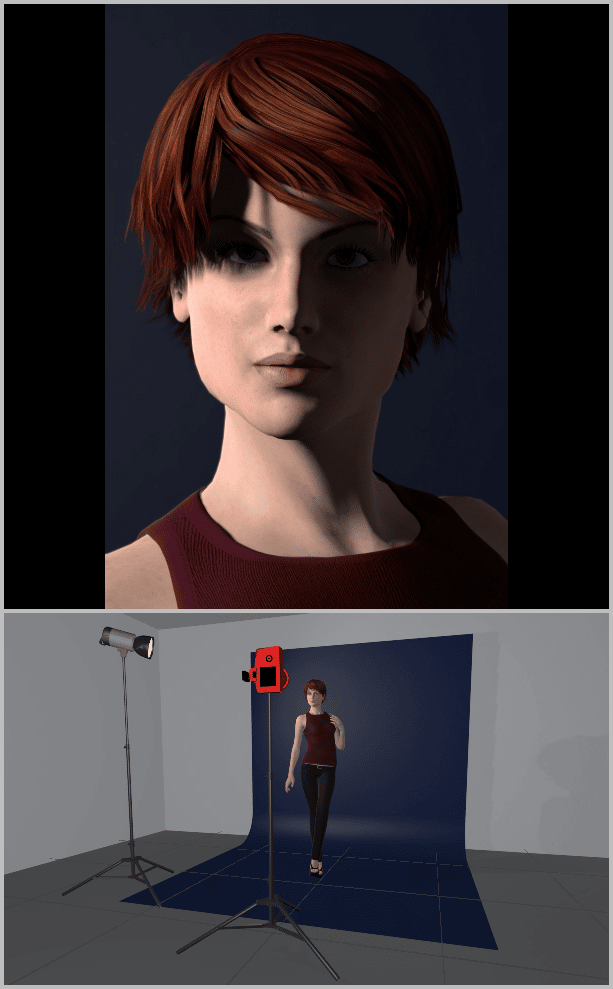

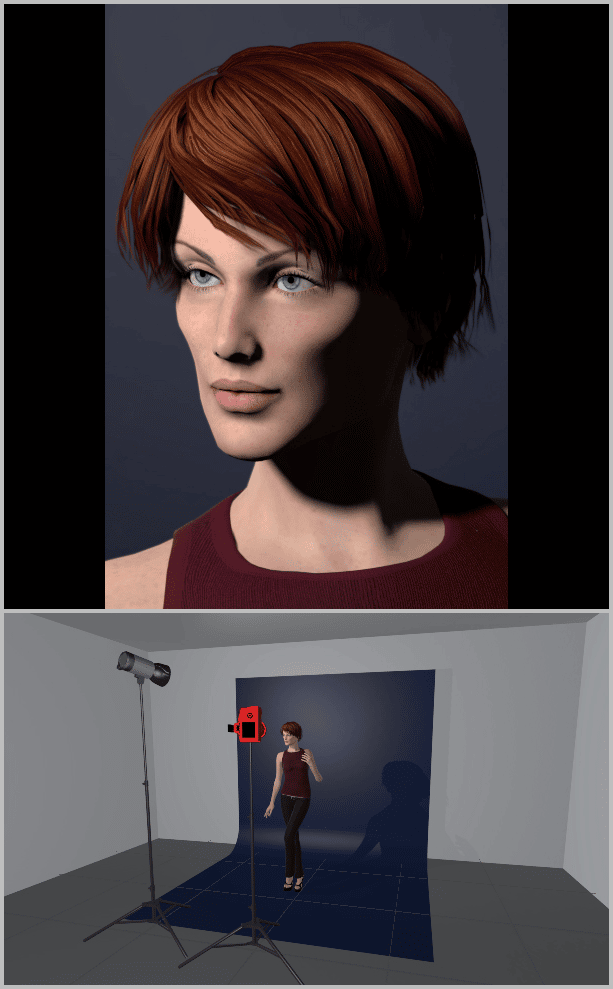

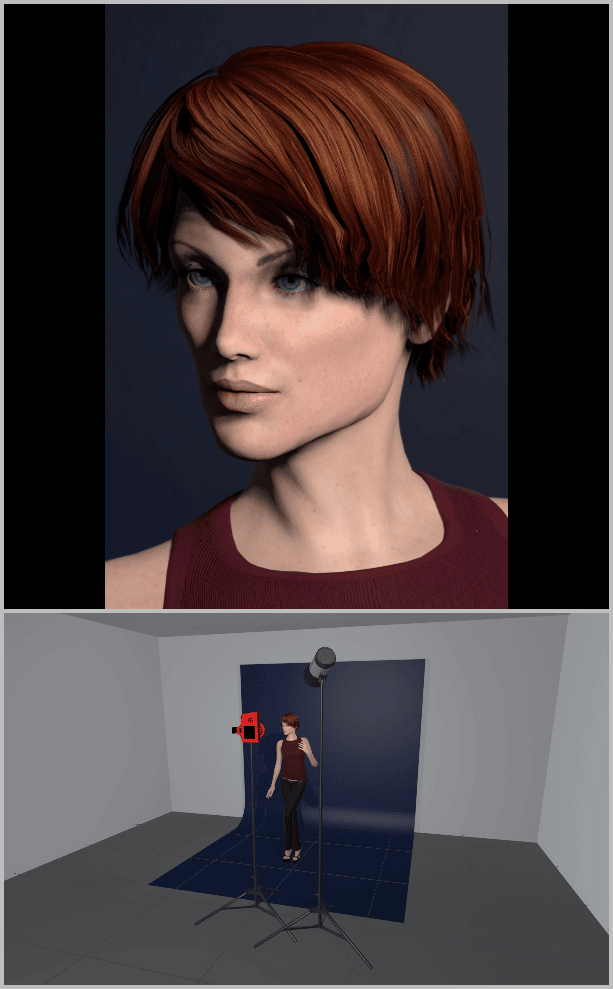

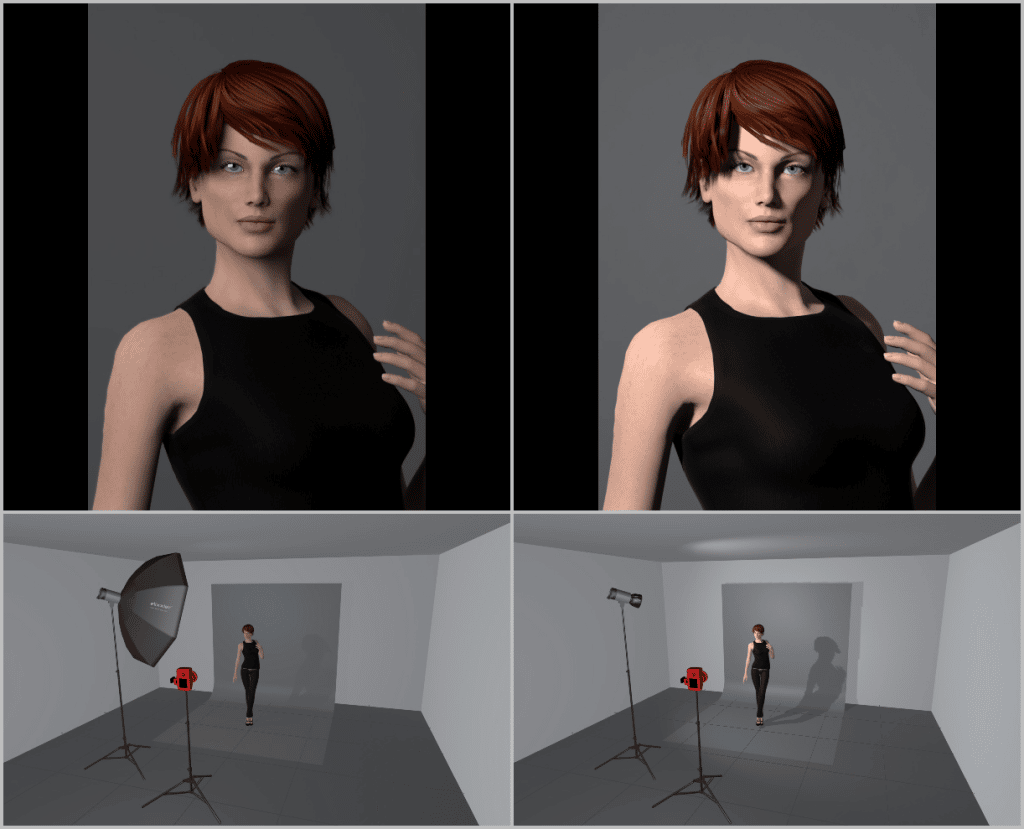

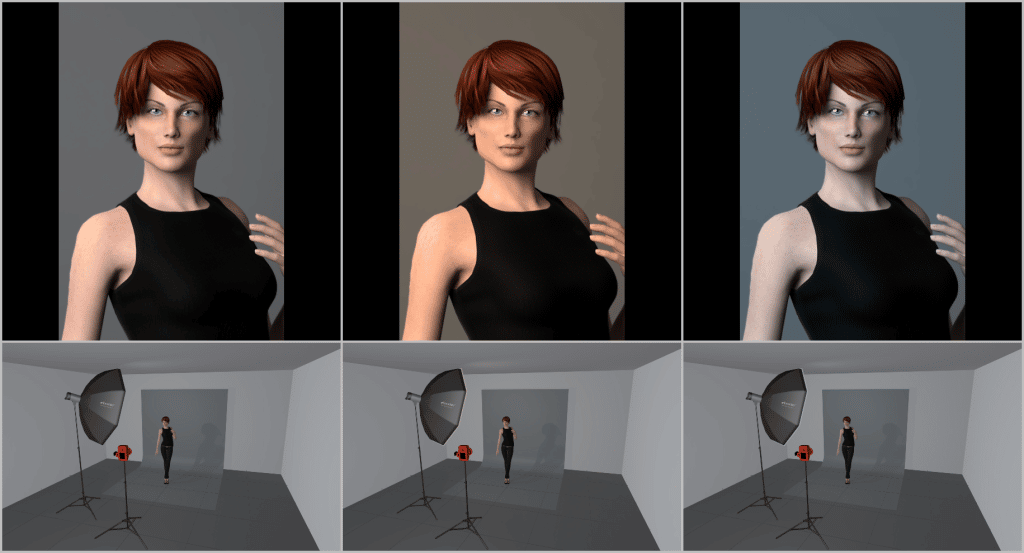

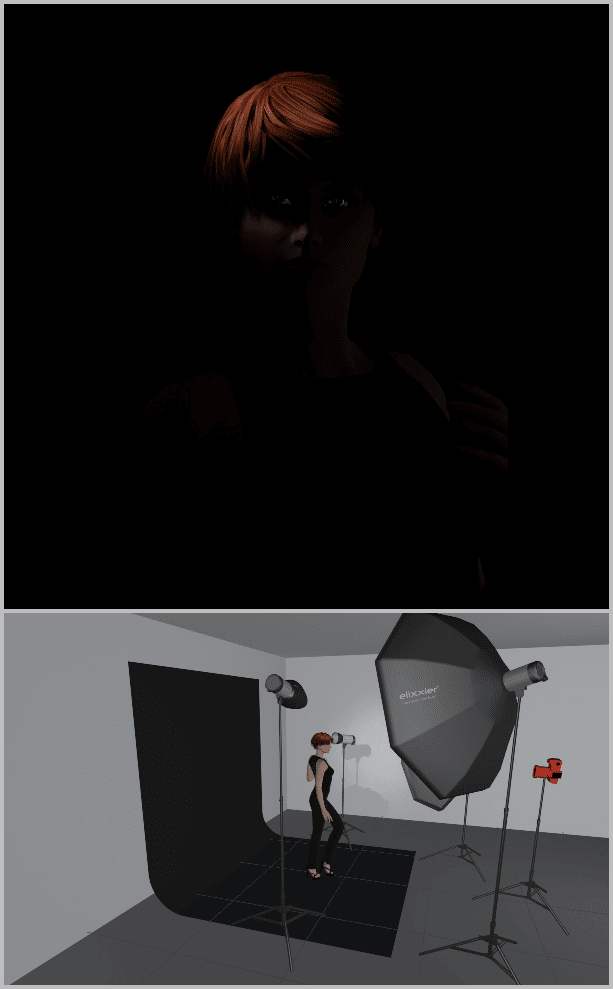

To make my examples more illustrative, I’ve used hard (sharp) light, which otherwise isn’t very flattering for portraits of women. I also haven’t supplemented it with other light to add a glimmer to the subject’s eyes (catchlight) and to soften shadows.

Rembrandt—the best-loved lighting pattern, one that gives portraits a certain drama. It gained its name from the renowned painter Rembrandt, who used it in his pictures. You can sometimes also encounter the name triangle lighting.

Here the subject is illuminated at roughly a 45° angle from the top and one side. One half of the face is illuminated, and the other is almost entirely in shadow, except for a small triangle below the eye.

Loop lighting—this lighting type is similar to Rembrandt, but the light source is not as far to the side. The shadow of the nose thus isn’t long enough to connect to the shadow on the face, and so no triangle of light is created.

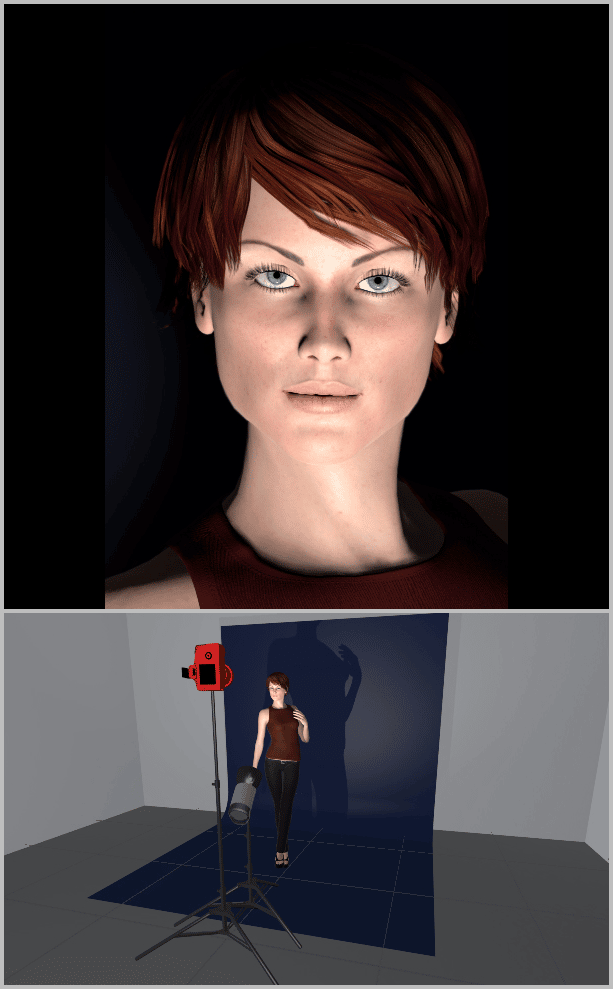

Butterfly (Paramount, Hollywood)—this lighting type is used by photographers in their portraits of Hollywood stars. The subject is lighted from the front and above, and so a light reminiscent of a butterfly is created under their nose.

Side lighting—dramatic lighting where you only light one half of the subject’s face. This definitely is not appropriate in cases where you don’t want to highlight imperfections on their skin.

Short lighting—with this lighting, you optically narrow the subject. Instead of facing the lens directly, they have their head turned slightly.

The key light shines from precisely the side towards which their head is turned. Thanks to this, the cheek that’s turned away from the lens is illuminated, and so it looks narrower. The cheek turned towards the lens, meanwhile, is in shadow and looks broader.

Broad lighting—the opposite of short lighting. Use it to add volume to the face of a subject whose face is too narrow.

Light the Subject from Above

Try at all times to place your light above the level of the subject’s eyes. The sun shines on us from above, and so light placed below eye level feels unnatural. So only light from below if you want to scare your audience.

Don’t Forget the Sparkles in Their Eyes

The eyes are the most important part of a portrait. A glimmer in them makes a portrait feel alive. If it’s not there, the picture feels dead.

Tailor your light placement to this fact. If you light from too high or from the side, your light will not reflect off of the subject’s eyes onto the lens. So when checking your light placement, think about these seeming details as well.

How to Light a Portrait Outdoors and Indoors

You’ll apply the above principles when photographing under all the light sources you can think of. Even though achieving the desired result will be harder in some cases than in others. That’s why in future articles, I’ll be showing you how to deal with individual lighting situations.