Jan Svatoš the “Photographing Director”: Film Fascinates Me; Digital Steals No Souls, But Eats Time

Jan Svatoš is a successful director of documentaries, and he’s earned a number of awards for them. But he also has no shortage of passion and talent in photography. He carries traditional analog gear with him on the road, and he won’t hear an ill word about it. Read on for our inspiring interview where he reveals what photography means for him and how he views it.

How, in your opinion, has photos’ meaning evolved from their beginnings until today?

After its invention in 1839, photography liberated the visual arts, took over the job of capturing reality, and paved the way for impressionism, but as art, it was long disrespected. Today things are completely different: the gradual democratization of this medium has made it so that nearly everyone can become a photographer. But it remains open to question what good all those billions of food and pet photos and selfies that we upload each day onto social networks will do for us and future generations. Really, the sheer quantity scares me. What I’m totally not seeing today is any kind of self-reflection on why we take pictures. The enlightenment philosopher Georg Lichtenberg once said: “A book is a mirror. If an ape looks into it an apostle is hardly likely to look out.” I’ve got a feeling that the same could be applied to photography.

The Native Americans say that being photographed steals your soul. What do you think about that?

To some extent they’re right, but photos definitely also steal the souls of us, the photographers. Today there’s a reigning feeling that every snap is free. But in reality the more photos we take, the more time we spend by our computers sorting, going over, backing up. From the financial standpoint every photo really is free, but from the standpoint of the time in our lives, we are constantly being robbed.

Many people are moving on from photography to video. What advantages and disadvantages does it have over photos?

It doesn’t seem to me like people are abandoning photos for video. It just seems that technology in cameras—and in phones—has advanced. They both now let us shoot both pictures and videos. The two have a lot in common; after all, film is just 25 photos a second. On the other hand, there’s also a lot separating them—a photo is a moment torn from time. Unlike a film in a theater, though, I can view it whenever I want, but it only has very limited possibilities for telling a story.

Where would you say the border is between an ordinary record of reality (whether that’s a photo or a video) and art?

The quest for answers to this fundamental question would be enough for a book of its own. That’s know-how that every artist guards carefully. Once upon a time they asked the famous Baroque composer and organ virtuoso Johann Sebastian Bach something similar. I love his curt reply: “There’s nothing remarkable about it. All one has to do is hit the right keys at the right time and the instrument plays itself.” There’s no room here for long-winded theories, but I do explain some of the principles in my workshops.

One of your photo courses includes a whiskey tasting. Do you think something like that can influence a picture if it comes just before the shot?

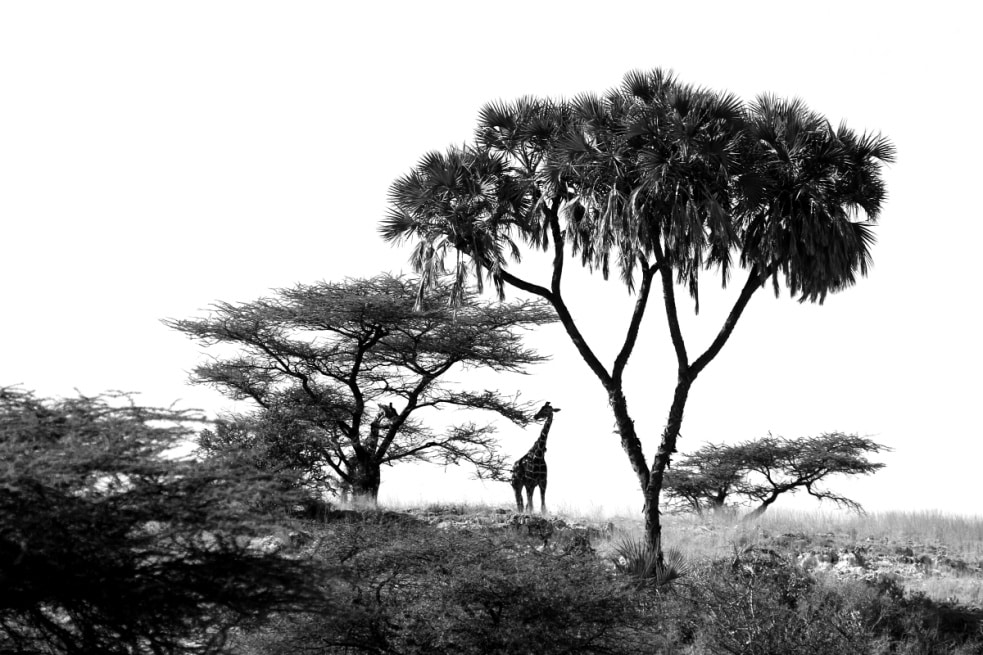

You’re talking about the workshop named Awakening of the Landscape that I hold in my native highland region of the Czech Republic. This course focuses on teaching not only photography, but also the techniques of old landscape masters, which I myself studied at Prague’s film and TV school FAMU under professor Bohumír Prokůpek. And as far as the whiskey itself is concerned, I’m a big fan of it, and it suits the Czech highlands just as well as the Scottish ones. Naturally the tasting isn’t before the shooting; it only comes at the conclusion of the day. I’m glad that, alongside the Photo Safari in Dvůr Králové, this workshop is one of people’s favorites, and one that they long remember.

What significance do old cameras have for you? Film cameras are the only kind you ever take with you for your nature photography. What’s the magic you see in them?

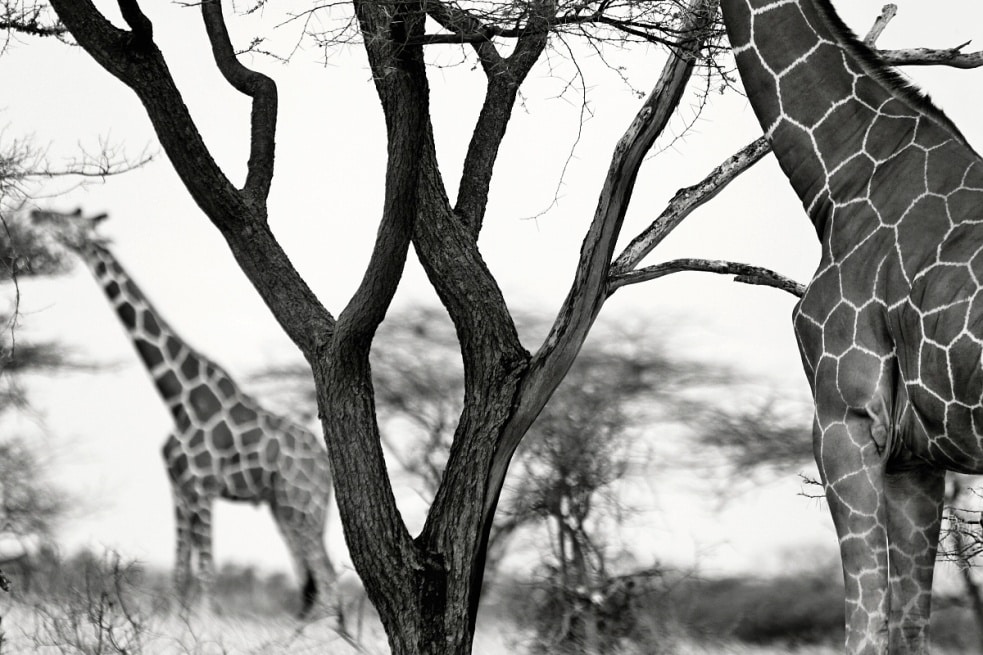

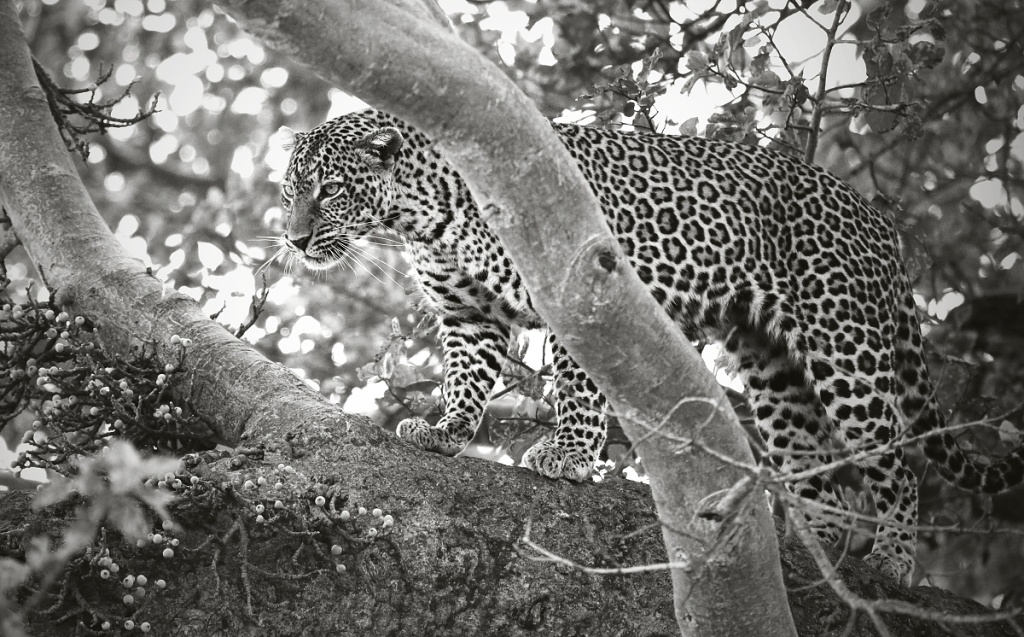

Film technology has fascinated me since I was little; Dad often took me into the darkroom, and that enraptured me. Today it’s equally as exciting for me to create a picture with analog in complicated conditions that test my mettle. That’s one reason why I organized a 40-day expedition in 2010 named Photographic Returns. Its participants and I headed out with a portable darkroom into scorched and inhospitable North Kenya, where there was neither any mobile coverage nor any infrastructure. What did I learn? That analog has the power to teach you the most important thing—to think before you press the trigger. Ultimately this journey led to a triple award-winner of a documentary: Africa Obscura. Shooting to film still carries a mystery that disappears in modern photography the moment your creation appears immediately on the LCD.

What idea would you like to someday capture and immortalize, but you haven’t had time yet?

It’s probably mainly a wide range of photo subjects that pile up over time. But because I’m superstitious, I never talk about these ideas in advance. Either the stars will align and they’ll become realities, or they’ll just exist temporarily in my head and then dissolve.

How does your work currently fulfill you?

I have the good fortune of being an independent filmmaker; I’m freelancing, shooting movies, writing. It’s creative work, and one major advantage of it is all the freedom. But I also enjoy organizing photo courses where I try to familiarize people with my rather non-traditional photographic philosophy. I reveal how to “take pictures” without a camera, how to face the digital avalanche, and even how to develop film in coffee, Filming has left me less and less time for teaching, but on the other hand I’m glad to see people rediscovering the experiencing of photography, and to see them coming back to my courses. This year, the graduates of my first Photo Academy talked me into opening up a seventh year of my evening school.

What are your plans for the summer months ahead? Will you be heading out to shoot pictures or movies somewhere?

I’m currently wrapping up the script for a new feature-length documentary named Once the Lion Roars, which will be a dual portrait of two inspiring figures of the Czech middle ages—king Ottokar II of Bohemia and the Bohemian pilgrim Odoric, who by the way was the very first European to have made it all the way to Tibet. We’ll be making field visits in Italy, Slovenia, and Austria. Telling stories in film always entices me to include “overlaps” into the present day, and things will be no different for Odoric, the forefather of all Czech travelers, and king Ottokar, who was a role model for the much better known King Charles IV.

Which photographic genre is closest to you, and which, on the other hand, isn’t your cup of tea?

I like documentary, landscape, and street photography; I like to take pictures of the wildlife and the local peoples in Africa. But nudes and portrait photography have their magic as well. I guess what hasn’t really captivated me is macro photography, and what I really don’t like is the type of wildlife photography that’s nicknamed “wildlife porn.”

How much time do you spend on editing photos? Do you have some kind of moral red line that you won’t cross in your edits? (Like deforming reality or retouching people…)

I still work from my experience in the darkroom, where we regularly did cropping and retouching and for example dodging and burning (done on a computer today). One barrier I just can’t cross, though, is adding something new to a photo—cloning the sky, inserting various objects, creating false light. I tend to spend more of my time on sorting and archiving. That’s where I appreciate Zoner Studio. It helps me to shift many of my decisions from the monitor into the field; that’s where I most like to spend my time.

Are you currently more of a photographer or more of a director?

I’m a photographing director. After all, I even take pictures when I’m shooting for a movie; I like to take “backstage” photos, document my tours of the terrain, and so on.

Often in movies emotions are key. Are they important for you in photos as well? And why?

A movie or a photo can catch your interest for a whole spectrum of reasons. Emotions are one tool for telling a story. But at the same time, you or I could be interested by a photo of a demolished countryside building that another viewer would dismiss as just a hovel. The theories of my favorites Roland Barthes and Ernst Gombrich really resonate with me in that respect.

How can people make the strongest impression on you?

If you’re thinking of humanity overall, it’s primarily people who have, through their lives, left a significant mark that reaches beyond themselves. That’s also where I see the point of documentaries: to point out the stories of remarkable and inspiring people who have drowned too fast in the sands of time. And actually that’s what my latest feature-length documentary, The Ark of Lights and Shadows, is about. It tells the story of two photographic pioneers, the husband and wife Martin and Osa Johnson, who significantly contributed to the rise of travel and nature film and the phenomenon of photo safaris. Actually it’s already available online as video-on-demand, and it will soon be coming out on DVD as well.

There are no comments yet.